A MOBILE LANDSCAPE

Ryan Walker / Vid Ingelevics. Toronto Port Lands, 312 Cherry St & Villiers St Median, Toronto, CAN. (06/04/2021 - 04/01/2022)

Installation Photos: Toni Hafkenscheid. Courtesy of Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival.

Since 2019, Toronto-based artists Vid Ingelevics and Ryan Walker have charted the progression of the Port Lands Flood Protection Project, one of the most ambitious civil works projects in North America. This second series of photographs installed on utilitarian wooden structures built for their CONTACT 2020 exhibition focuses on the complexities of excavating a post-industrial site and the resulting environmental cleanup.

A Mobile Landscape offers views of the vast, dynamic waterfront landscape lying behind the construction hoardings, and therefore unseen by the general public. Giant mounds of dirt suddenly appear on site, then vanish. Piles of rocks, metal, and concrete materialize in one place, only to appear elsewhere days later, thus creating a landscape that is always in flux. Ingelevics and Walker capture some of these fleeting moments on a site they describe as “a different planet” every time they visit.

In total, 1.3 million cubic metres of soil will be excavated for this project—enough to fill the Rogers Centre—and most of it will be recycled. What looks like a war-torn, sometimes lunar, wasteland is in fact a sophisticated and tightly choreographed scene. Mobile Landscape #9 (mounds), 2020 shows the variety of material piles that have been tested for quality, classified, and separated. They are tracked as they move around the site, waiting to be treated or recycled. The mound of clean drainage sand in the foreground of Mobile Landscape #5 (river valley), 2020 will line the newly excavated Don riverbed, visible in the background. These piles are transient, but so is everything else on site: human and machine imprints, materials and textures. In Mobile Landscape #6 (geotextile), 2019, a black sheet lies atop a layer of compacted soil to avoid the mixing of different quality soils. These strange textures and materials will eventually be covered over by the construction process as the entire site is “naturalized.” Historical uncoverings add another layer to the functional transience of the site. In Mobile Landscape #3 (breakwater), 2020, an archeologist measures a breakwall built in the late 1800s, the top of which once supported horse-drawn wagons, automobiles, and hydro lines for local cottagers to make their way to Fisherman’s Island, which has since long-disappeared.

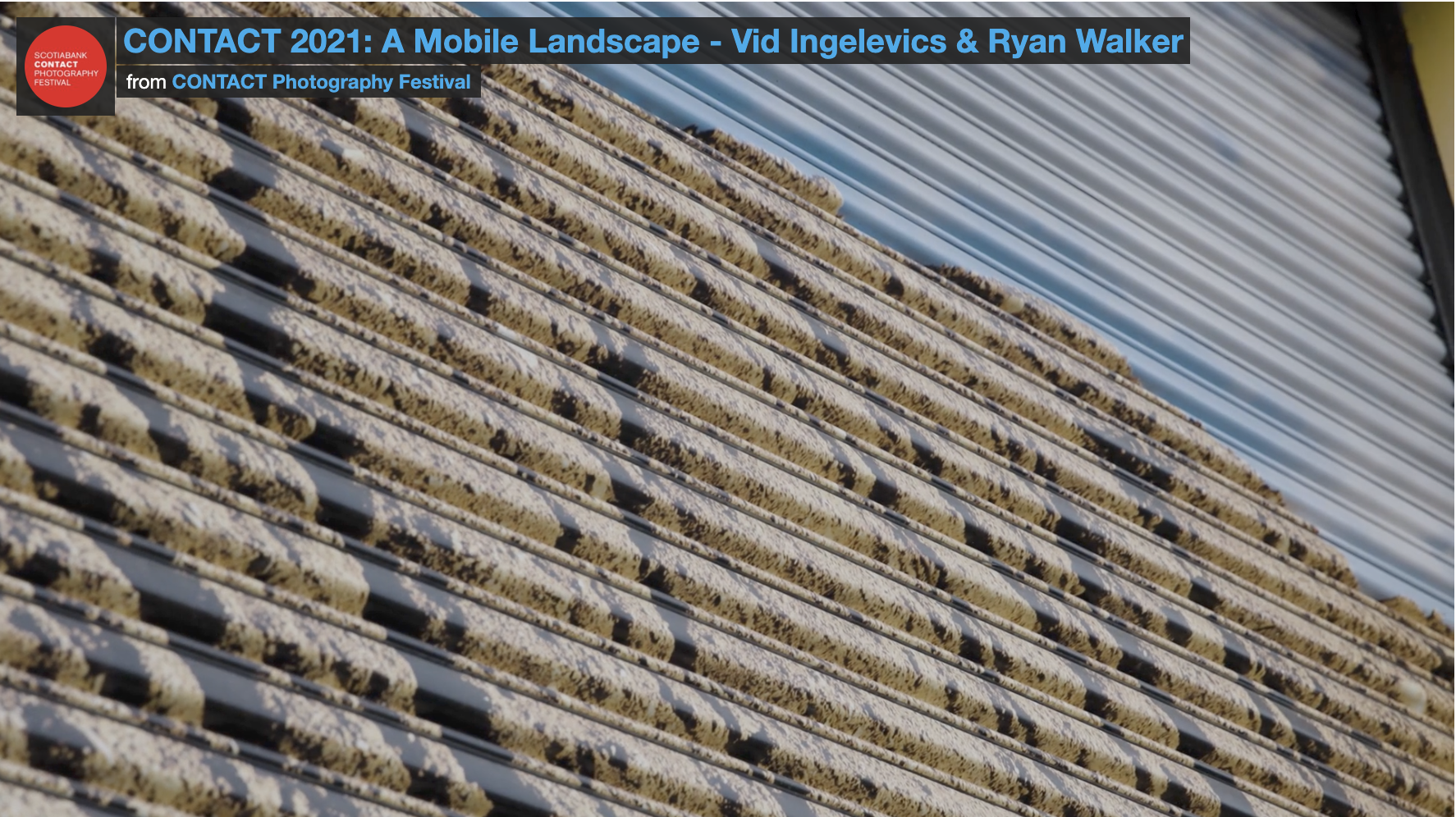

One of the extraordinary effects of capturing this expansive, fluctuating landscape is that all sense of scale can easily be lost. Images turn abstract and ambiguous within the limitations of a frame: snow-covered soil mounds could be the Himalayas; runoff on a soil pile recalls the Badlands in Utah or Alberta. That is, until we recognize a piece of debris, or the tip of a crane, or a nest of rebar, or a small figure standing somewhere in the photograph, which snaps perspective into focus. The images in A Mobile Landscape hold viewers in a liminal, metaphorical space where, for a moment, one thing could be anything.